The Brazilian government response to ever-growing favelas

- André de Botton

- Jun 15, 2021

- 3 min read

Updated: Jun 16, 2021

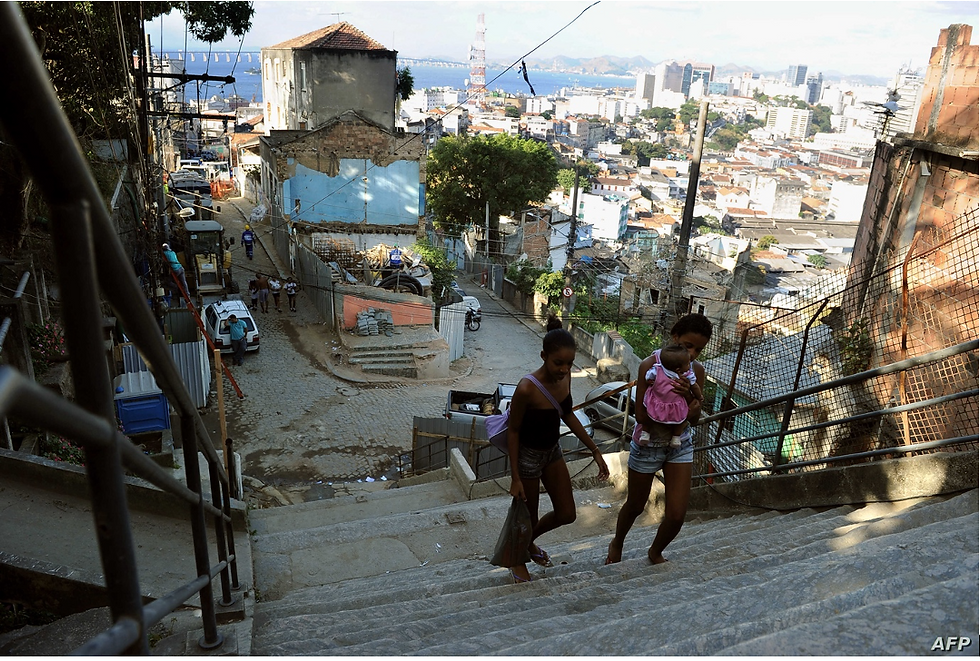

In Brazil, due to several economic and social push and pull factors, a mass of internal immigration from North east Brazil to the more industrialized and developed South East started occurring in the 1970s. With this new wave, came the need of rapid urbanisation in the major cities. However, resources and manpower were unable to keep up with the ever-growing low-income population, forcing the migrants themselves to build temporary housing without the proper means to do so. These settlements, which are in their majority located in steep hills, eventually grew in size to become what we now know as overcrowded “favelas”. This is one of the reasons why Brazil has one of the highest housing deficits in the world, as around 7 million families live in units which are deemed not to have adequate conditions to be habitable, as they are most of the times constructed by people themselves using basic materials such as tarpaulin, scrap wood and corrugated iron. (O Globo, 2016)

In 2018, a study conducted by the UFRJ university (Federal university of Rio de Janeiro) found that about 2,200,000 people live in favelas in the city of Rio de Janeiro and its surrounding suburban areas. That is approximately 14% of the city’s entire population. The social-economic impacts of this are tremendous, as families with improper housing are found to be 84% more likely to take children out of school in order to work and provide for the family, according to IBGE (Brazilian Institute for Geography and Statistics). Without proper education, their jobs options are often limited and poorly paid. This then results in families getting caught up in the poverty cycle, and with a structurally limited supply of income. Apart from this, most of these community’s lack adequate access to transport networks and social services, apart from having no access to proper electricity, clean running water, rubbish collections and hospitals. These factors further spiked discontent citizens demand for a government response to this ever-growing problem.

This then prompted the Brazilian Federal government to reach a consensus with all other state governments in 2009, which marked the creation of the program we now know as Programa Minha casa, Minha vida or PMCMV. It was a program created with the intent of tackling the poor housing units in favelas all over Brazil by subsiding the acquisition of a house or apartment for families which have an income up to 380 euros per month. The program is subsequently divided into 4 different stages of amount of aid provided, which is directly proportional to the family’s amount of income. Family’s with less income or more children for instance, may be applicable to receive better deals for payback upon receiving the house from the government. The range of assistance to the different socioeconomic groups is huge, as in the lowest group for example, up to 90% of the property can be financed by the government, and the remaining 10% will only be needed to payback in 10 years’ time, with zero interest applied. Whilst in the top income earning group, the government does not subsidize anything, the only difference being that the family at hand will only have to pay it in 30 years, and with a below the market interest of 5%. (Caixa, 2017)

On the other hand, there are several people who claim that this program is nothing but a false hope, where people do not properly realize where they are stepping into. Firstly, due to their immense concentration and isolated location, urbanists and experts believe that it further creates ghettos of poverty of the future, as they are supplied by a poor public transportation system which consequently isolates them from the CBD (central business district) during weekdays, and from a proper nightlife on weekends. (Estadão, 2015). Construction quality of these properties has also found to be faulty over the years, as construction companies attempt to spare every money, they can with bad quality materials and poor infrastructure. After just a year in their residence, residents have reported things such as cracks in the wall, no proper running water in sinks and no power in outlets.

In conclusion, we may now understand how although this program was created with the right intent and really strived to solve the overpopulation problem in favelas, when implemented, it failed to do so due to political schemes and lack of investment on something which would truly be impactful and enduring. Now, after several powerful politicians and businessmen being arrested, and the Brazilian government suffering a new reorganization by the new president, I cannot help but wonder if this time around the program might end up being more effective. It is only fair we give the program which offers a second chance to the public, a second chance itself.

André De Botton

Bibliography:

Comments